Historical evidence regarding the libraries of muslim Spain

I'm talking about Europe. Especially about Muslims within Europe, and now I am not mentioning the 1% extremist, which is a disgrace to everyone, although this 1% disgrace is also present among the "pure" inhabitants of Europe. I’m talking about the normal majority who strive for coexistence.

While a cleaning lady wearing hijab cleans the toilet of a CEO of a Parisian company or changes a diaper in a nursing home for elderly, it is said: ouch! what a cute lady is Leila, or Fatima! However, as soon as their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, who were brought up in European schools, are aware of their rights and therefore dare to open their mouths, dare to represent themselves, the hijab proves to be an evidence of extremism and banned in an instant. This and such an infantile response are given by Europe for issues that root much deeper.

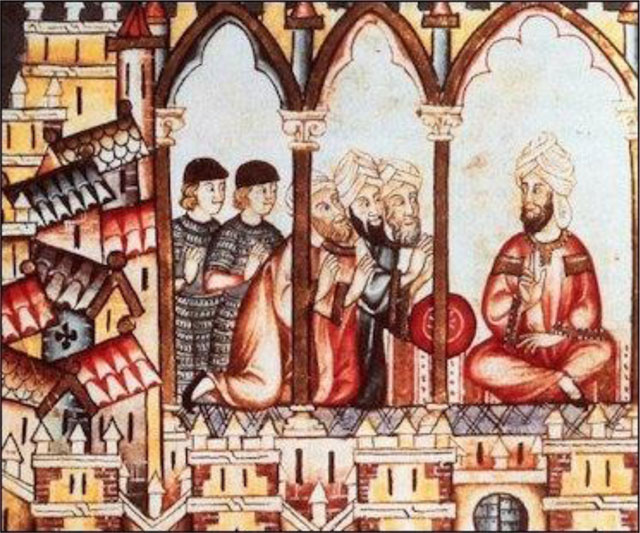

There is a conservative view that Islam is foreign to Europe. This is a new phenomenon, they say, it has only been present for a few decades. From the point of view of Europe, they have always been considered an attacking force, a conqueror. The answer to this is that between 711-1492, Islam was present in Iberia not only as a raiding army, but as the establisher of a prosperous empire when the rest of Europe did not even know what soap and the book were. I'm going to mention only a few words about this period below, and I will not go beyond 1492, even though there has taken place since then also fundamental influences on thinking, science and art in several European countries, which are present through Islam and Muslims.

Let me publish an excerpt from the following paper:

https://everything2.com/title/Historical+Evidence+Regarding+the+Libraries+of+Muslim+Spain

By 762, expansion under the Abbasid dynasty (ca. 750-1258) had slowed, and the rulers in Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo and Cordoba could survey their empire's peaceful boundaries, stretching from Asia to the Atlantic. Their attention turned to domestic matters rather than expansion. Baghdad, under the Caliph al-Ma'mun (770-813), was made home to the empires first formal academy and library. Modeled to some degree after the Alexandrine model, it was devoted to the transcription and translation of poetry, science, philosophy and theology. In 788, the construction of the colossal Royal Mosque of Cordoba, with its attached school and library, was underway. By 794, paper mills were being constructed along the rivers around Baghdad, with that precious material being shipped to all the capitals of Islam. Book production in the east blossomed into a vital industry as textual materials, translators, scholars and tradesman all spread throughout the Near East and Mediterranean. A new sector of the economy was born, specializing in acquiring, duplicating or locating rare books. The new libraries and colleges of Spain were no exception. The prestige of one's city or royal library led to a spirit of noble competition between the caliphs, viziers and deputies of various provinces, each wishing to attract the brightest scholars and rarest literary talents. Andalusia was, above all, famous as a land of scholars, libraries, books lovers and collectors…when Gerbert studied at Vich (ca. 995-999), the libraries of Moorish Spain contained close to a million manuscripts…in Cordoba books were more eagerly sought than beautiful concubines or jewels…the city's glory was the Great Library established by Al-Hakam II…ultimately it contained 400, 000 volumes…on the opening page of each book was written the name, date, place of birth and ancestry of the author, together with the titles of his other works. Forty-eight volumes of catalogues, incessantly amended, listed and described all titles and contained instructions on where a particular work could be found.

The libraries, in turn affiliated with a sprawling network of copyists, booksellers, papermakers and colleges, churned out as many as 60, 000 treatises, poems, polemics and compilations a year. The head librarian at Cordoba, Talid, personally appointed to the mosque collection by al-Hakam, employed a female Fatimad deputy named Labna, who acted as the Library's specialized acquisition expert in the bookstalls and merchants of Cairo, Damascus and Baghdad. This level of industry was in sharp contrast to the knowledge production underway throughout much of Christendom, where during the same period the two largest libraries (Avignon and Sorbonne) contained at most 2,000 volumes as late as 1150.

To return, as discussed at the beginning of this essay, to the motif of requisite social conditions for the development of libraries and historical record, we can see the Europeans were at a vast disadvantage when compared with the Moors of Spain. Natural disaster, political violence, disease, theft, neglect and poverty all took a heavy toll upon monastic book production throughout Europe during the 7th and 8th centuries. The manpower and resources required to train a scribe, supply him with bed, ink, parchment and food were (on a page-per-page basis) incredibly high until well into the 12th century when some level of peace, literacy and prosperity began to revive Europe. Andalusia escaped these many of these hardships for almost five continuous centuries, providing its literary industry with almost uninterrupted economic stability from the early 8th to mid 13th century: …literature acquired a new seat at the library of the Umajjades sic? in the Spanish town of Cordoba…Al-Hakam II in the tenth century had books brought in large numbers from all parts of the Islamic empire, and in his palace kept numerous scribes, editors and bookbinders…later the Arabic translations where again translated into Latin, and several famous classical authors, including Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen were, in part at least, made known to European scholars of the Middle Ages in this round-about way.

It was only with the Reconquest of Spain and Sicily by the Normans in the 13th century that much of this material was closely scrutinized by the Church, or physically removed for 'safekeeping' in the new universities or palaces of Europe. The scribes of Christendom had never seen anything like the wealth of knowledge produced under the reign of the Spanish Arabs. The introduction of the more economical paper medium was also, as noted, a crucial boost to European literacy. Compared to their monastic brothers in the north, the secular Arab scribes also had the benefit of much wider literacy, as well as unhindered trade access to all manner of bibliographic materials (ink, paper, etc.) from the East. One aspect of manuscript production by Arab calligraphers and scholars we have not yet mentioned, however is quality , more specifically 'quality control', what medieval Europeans would later utilize in their legal concept of the authentica habita, or specifying an original document of privilege. Early European medieval readers equated a book's writer with a sort of human 'transmitter, much in contrast with the modern sense of author as authority.' The Arabs, on the other hand, developed an entirely different scheme.

As outlined, by 794 paper mills in Baghdad had dramatically decreased the cost of textual material throughout the Empire. Even 'popular' literature, as a credible genre, was fostered by a rising level of literacy (the first versions of al-Rashid's Arabian Nights are dated from this era). In 813, the Bait alHikmah ('House of Wisdom') was established in Baghdad (with its own libraries, laboratories, transcription service and observatories), an institution the likes of which Europe would not develop for another three hundred years. Reportedly, by the late ninth century, there were a hundred book and paper shops in the Waddah suburb of Baghdad alone. By 976, the library of Cordoba was said to have employed 500 librarians, scribes, physicians, historians, geographers and copyists; the catalogue had swollen to 44 volumes, arranged by subject, then order of acquisition. There was no difficulty in acquiring new materials as titles moved freely from Byzantium to Baghdad, Cairo to Cordoba, by way of Venetian and Arab shipping routes. Maintaining the quality of the copy was another matter

To address this issue, Arab scribes developed numerous strategies to deal with the imperfections of bibliographic transmission, much to the benefit of their libraries. First, specialized glossaries, vocabularies and dictionaries for each area of knowledge, be it history, poetry, literature or medicine, were carefully researched to better the standards of spelling, grammar and usage. The compilation of textual material, often gathered in the lecture or reading rooms of the libraries built throughout the empire, frequently led to transcriptions of scholarly discussions, intermingled with other research, and given a final gloss by the scribe himself. These compilations often became books. The authority to write these books came by way of a 'certificate of audition', an actual notarized document, which asserted the writer to have schooled successfully upon the subject. This credential, called Arabic samã', served to authenticate the 'authoritative transmission, or isnad of a book, giving evidence that the person or persons named…had studied the work under the direction of the author…belonging to a chain of transmitters going back to the author.' A copy of the notice was placed inside each manuscript to attest to its value and precision as a information source. This system of certification and accreditation was necessary given the mass of literature being produced, and increasing level of scribal apprenticeship evident throughout the Eastern and Western Arab world. According to some chroniclers of Andalusia, Hakam II (966) founded three schools attached to the Great Mosque and another 24 in the city's suburbs before the end of his reign. Pupils would, after the allotted time and success, be issued ijãzah diplomas which attested to their standards of tutelage and qualifications for administrative, diplomatic or scribal postings (usually in the government). The postings offered were by no means exclusive to male students. Ibn al-Fayyãd, one historian of the time, notes that in one eastern suburb of Cordoba, the Mosque authorities employed 170 women solely to make Kufic copies of the Qu'ran. By that time, textual knowledge had attained a special position in Moorish culture, reflected in the importance given to book scholars. Librarians had risen to such administrative and cultural power (as they were frequently authors and scientists as well), that such posts were exclusive to the most wealthy and powerful families. One 10th century account of an Arabic 'house of books' runs thus, …the library constituted a library by itself; there was a superintendent, a librarian and an inspector chosen from the most trustworthy people in the country. There is no book written up to this time in whatever branch of science but the prince has acquired a copy of it. The library consists of one long vaulted room, annexed to which there are store rooms. The prince had made along the large room and the store chambers, scaffoldings about the height of a man, three yards wide, of decorated wood, which have shelves from top to bottom; the books are arranged on the shelves and for every branch of learning there are separate scaffolds. There are also catalogues in which all the titles of the books are entered.

The Eventual Fate of the Cordovan Library of Caliph Hakam II.

Just as historical circumstances conspired against the imperial sense of permanency which afflicted many Roman administrators, eventually disintegrating their hold on the provinces of the Mediterranean, so too did Arab rule of the Iberian province begin to falter in the first decades of second millennium. Internal political divisions between factions in Cordoba, Seville, Fez and Baghdad spread from palace courts into mosques and then finally onto the streets. As early as 909, Fatimad supporters in Egypt banded together to seize power from the imperial rule (centered in Baghdad) by wresting control of the mosques and schools. In effect a political struggle, its rhetoric took on highly religious overtones. The North African movement (which soon spread from Egypt to Morocco and Spain) used religious orthodoxy and charges of moral laxity to attack their Arab rulers. In many cities, the strategy worked. An increasingly doctrinaire spirit spread throughout the empire (leading to several book burnings and sectarian inquisitions in Baghdad ca. 923) and by 969 the Fatimad Berbers, ascribing to Ismaili doctrine, took command of Egypt. Meanwhile, by 966, Norman raids had begun from the North on Western Spain, hostilities had broken out between Sicilian and Andalusian navies, and by 1016 Pisan and Genoan fleets had launched an effort to retake Sardinia.

With these drastic changes, the unchallenged cultural peace of Moorish Spain vanished. Internal power struggles and external naval competition accelerated throughout the Mediterranean as the communes of northern Italy established merchant fleets of their own. This heightened sense of competition finally allowed the Berber population (ruled Arab Spaniards but actually indigenous to North Africa) to openly revolt. In 1031, the conservative backlash which had begun in Egypt over a century beforehand swept the Umayyad dynasty from power in Spain. With the removal of the long-standing al-Hakam family, effective cultural leadership over the region receded to individual cities, such as Toledo and Seville. Some reports state the great Library of Cordoba was broken up, or even burned, by the Berber insurgency after the expulsion of the Arabs from that city. As chaos spread, the defensive line which insulated Andalusia from Europe faltered, and between 1085-91, Toledo, Sicily and Sargasso were all occupied by Christian armies. In 1095, seeing the successful mobilization of European forces in Spain, and hoping to revive Christendom, Pope Urban II declared the Crusades. Cordova itself would not fall to Christian siege until 1236 however, and it was actually during this period of political and religious conflict that much of the cultural exchange took place through the scholarly pilgrimages Averroës and Michael the Scot. Yet by 1248 all of Eastern Spain had fallen to the Crusaders. This new regime enable a wave of Jewish and Christian translation, particularly of the 'lost' Greek sciences, in what one scholar terms 'the invasion of Aristotle.' So began the great resurgence of European thought and science: Over a period of roughly a hundred years (1150-1250) all of Aristotle's writings were translated and introduced to the West, accompanied by a formidable number of Arabic commentaries…this amounted to a vast new library. The work of assimilating and mastering it occupied the best minds of Christendom and profoundly altered the spiritual and intellectual life of the West…such masterful Arabic commentators as Avicenna and Averroës - who emphasized the unreligious and unspiritual character of the philosopher's thought - precipitated a grave crisis for the intellectual leaders of the West…harmonizing all of it with the Christian faith constituted a tremendous task…it inaugurated a period of unparalleled intellectual activity that reached its climax in the 13th century, especially in Paris and Oxford.

Despite the turmoil caused by both the Crusades and Reconquest in Spain, the scholarly interchange between the cultural centers of Andalusia and Europe actually intensified during this period. Two vastly divergent cultures were thrust together by conflict and commerce. Individuals involved in planning, negotiation and trading desperately needed insight into the mind of the Other; 'thus in the midst of negative attitudes and divisiveness, resulting from long-standing confrontation, a great deal of cultural interaction and borrowing took place.' By 1275, Christianized Arab merchants had established the first paper-mills in Christian Spain and Italy; fifty years later, the University of Paris alone employed 10,000 copyists. This exchange continued largely unhindered, until the dark days of the Inquisition; by then however, the spirit of inquiry and reason had blossomed throughout Europe, and humanistic spirit rescued from the myriad threats presented to the ideas found in the books of Iberia.